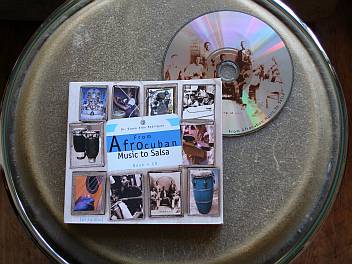

From Afro Cuban Music to Salsa

Dr. Olavo Alen Rodriguez (1998)

Pub. Piranha Records (Berlin)

This 180 page CD sized book comes with a 76 minute CD containing 26 Cuban songs, each representative of musical styles discussed in the book. The author worked for the Cuban Ministry for Cultural Affairs, has written much on this subject area and is well regarded internationally as an expert in the field. Contains over fifty pictures as well as a reasonably detailed discography for those wishing to delve further into each of the musical styles described. First published in Spanish (along with two audio-cassettes) by Cubanacán of Puerto Rico in 1992, with a different introduction by Pedro Malavet Vega.

Why you might buy it:

Handy, pocket sized guide to Cuban musical styles, written by a recognised expert in the area, the CD/Book combination make this good value for money, the layout is great – features a working flickbook; hands playing conga, great pictures, extremely “nice” as a thing in itself. The CD is not just a bonus item, the tracks are related directly to the text and help give the reader enhanced understanding. A none-too taxing read and a book that you might want to consider as a starter/primer for more in depth reading later on.

Why you might leave it:

This is quite clearly a book with a strong Cuba-centric slant. The musical influences of the Dominican Republic, Haiti and significantly Puerto Rico are hardly mentioned, the latter in fact gets no mention at all, timba doesn’t get a look in either. At times it needs a re-read, perhaps it has suffered in translation in places – much of the writing feels cumbersome to English speaking eyes (try and work that one out!). Difficult to follow up on the discography as many items are pretty hard to get hold of. Use of the word salsa on the cover misleading (depending on your point of view) as modern Cuban music seems to be what is meant by this.

Contents:

Preface

Antecedents

Musica Afrocubana

The Main Categories of Cuban Music:

– El Son

– La Rumba

– La Cancion Cubana

– El Danzon

– El Punto Guajiro

La Musica Cubana

Annex (discography/bibliography/musical selection; CD notes)

Selected extracts (from):

(preface by Alessio Surian):

Music travels – and Cuban music hits you with that nomadic spirit of music at its best. It brings together traditions and instruments from very different areas of the world; it sings of African roots catching on in the island’s fertile ground, of the meetings with other European, Caribbean and American traditions. Music is such an essential element of Cuban life that some of the best poems are not called “poetry” but “son”, the island’s most popular musical style. It is music deeply rooted in the life of rural and urban communities and as such it has fought its liberation struggles: just think of the popular pressure that forced the authorities to lift the ban on the son in 1920. It is music that moves both mind and body. Its dancing steps ask for all your concentration if you want to keep the pace of its polyrhythms.

And yet your mind may wander… who is Changó? is Okonkolo the son of Ya? is son the father of salsa? how many rumba styles are there? Well, relax! It makes listening easier and this text will provide you with all the answers.

…snip…

After an introduction on the roots of Afrocuban music, the variety of Cuban popular music is clustered around five main styles: son, rumba, Cuban song, danzón and punto guajiro. It is a fascinating story that spans over five hundred years and concentrates mainly on the last two centuries. It gives the son the most prominent role and it claims that it is the son and not the danzón that should deserve the title of “Cuba’s national dance”. You are invited to try them both before taking a stand.

Will this book help you in finding a simple definition of Cuban music? I doubt it. Some say that Cuban music to be really good must have sandunga, a word probably made of salt in Andalusian (Southern Spain) and ndungu, black African pepper. But why look for a simple definition while you still have a fascinating journey ahead of you? Get your feet ready for a wide variety of dance-steps and let the book and the music take you into the marginalised urban areas that created the rumba.

…snip…

The cd selection surely takes advantage of the almost thirty years of field-work experience by Dr. Olavo Alén Rodríguez. Cuba has no North and no South. Its compass only includes East (Santiago) and West (Habana) and they are well represented in this musical selection, not forgetting some of the island’s great musical geography, Matanzas, Cienfuegos, Guantánamo, Pinar del Río. From Miguel Failde to Ignacio Piñeiro, from Sindo Garay to Pablo Milanés, some of the most outstanding Cuban composers have their songs interpreted here by a variety of groups.

(Antecedents):

In the two centuries immediately following its discovery a great many Spaniards – Andalucians, Canary Islanders, Castillians, Extremandurians, Leonese, Navarrans and Basques – came to Cuba. Later, in the 18th and 19th centuries, waves of immigrants also came from Asturias, Galicia and Catalonia. All emigration activities were centred in the Casa de Contratacion of Seville.

The majority of these people came to Cuba, especially in the early centuries, only in transit to the American continent, for their objective was the lands of the New World. Ships sailing from Spain to the New World via Cuba used to stop over in the Canary Islands facilitating the migration of the local inhabitants. Thus, while people from all over the ethnic communities of the Spanish mainland arrived in Cuba, it was the people from the Canary Islands who settled here in large numbers, and had the greatest impact on the formation of the rural population of Cuba.

(Musica Afrocubana):

The bata drums in Cuba are always played in sets of three and they have two skins. The performer sits and holds the drum horizontally on his lap so that he can strike either side at will. The tension of the skin is fixed with tensors, generally made of rawhide. Sometimes bronze jingles are put into the iya. These rattles are known as chaworo. The believers say that the bata drums have a sectret called the ana. They suppose that the ana is an orisha that comes into the drum and prefers to live in the iya. That is why in Santeria these drums are considered sacred from the very moment they are built.

(El Son):

The lyrics of the son became so closely identified with its musical language that many Cuban poets – the most important of which is, perhaps, Nicolas Guillen – wrote musicless lyrics without losing the essence of the son in the course of artistic creation. Nicolas Guillen’s incorporation of this technique is perhaps one of the reasons he is today Cuba’s National Poet.

The aesthetic values of the son went beyond its musical framework into the field of artistic expression: dance. Many local variants were developed to dance to the son, and some of them spread throughoutthe nation, and were accepted and developed among the most diverse sectors of the population. This may be the reason that this genre is so popular in Cuba; dancing to the son became synonymous with dancing to Cuban music, because the motions of the dance began to identify the aesthetic characteristics of Cuban popular dancing much better any other Cuban music. In fact, in the lyrics of some sons there are references to the motions as elements that charachterise a very specific Cuban artistic behaviour. “La mujer de Antonio camina asi, cuando va a la plaza y cuando va al mercardo camina asi” (“Antonios wife has a walk like this, when she does her shopping, or goes to the market she walks like this”). This is part of the lyrics of a Cuban son which very clearly illustrates how this way of walking and moving was becoming a specific form of aesthetic behaviour of Cubans.

(La Rumba):

It is common in African religious music, and also in the majority of Afrocuban music, that the free improvisation serves as the centre of the polyrhythmic event which takes place in the lower planes and registers. Because of this, the constant rhythms, or the fixed and repetitive rhythmic patterns that may be called “accompaniment”, take place in the upper plane. When compared with European musical conceptions we find that this distribution of musical functions by registers is the exact opposite. The rumba faithfully preserved the polyrhythmic conceptions in the execution of membranophonic instruments which it has inherited from the African way of playing drums. By changing the way one strikes the drum skin one can achieve changes of timbre. The constant variation of these forms of playing the drum during the performance led African music toward polytimbric conceptions that were practically unknown to Europeans.

(La Cancion Cubana):

Along with the criolla, there appeared another genre known as the guajira which used an alteration between 6/8 and 3/4 meter. This produced effects that were very similar to what Cuban country people produced when they played plucked-stringed instruments. The criolla also used 6/8 and 3/4 meter, but it did so simultaneously: 3/4 meter for the accompaniment and 6/8 for the melody line. The lyrics of the guajira also alluded to the countryside, to its scenic beauty, and gave an idyllic view of the social situation of country people in Cuba (Ex. 15 – CD).

(El Danzon):

The fact is that the cha cha cha appears to be a variant of the danzon. It retains a structure very similar to that of the danzon for, although it avoids the rondo form, it does so only through an internal transformation of the rhythmic-melodic elements used in composing each of its sections. The cha cha cha even retains the feature role of the flute i.e. it is responsible for the solo part, and the improvisation, almost exactly as it was in the danzon.

Another important element taken by the cha cha cha from the danzon is the management of the timbric planes in the instrumentalisation. The violin melodies alternate with those of the flute, and the vocalist in practically the same manner as they did in the danzon and the danzonette.

In fact, the main difference between the cha cha cha and the danzon is the rhythmic cell from which the genre takes its name. Cha cha cha is an onomatopoeic rendering of the two rapid beats followed by a longer one (two quavers followed by a quarter).

(El Punto Guajiro):

Punto melodies are known as tonadas. Within the sphere of the punto libre, the melodic variants known as tonada menor and tonada Carvajal (also known as the Spanish tonada) are especially interesting because in the entire generic complex of the punto they are the only ones done in a minor mode. Another interesting factor in these tonadas is that they reveal the use of melodic phrasing and other stylistic aspects in the interpretation that have very obvious antecedents in the ways of singing of Andalucia and the Canary Islands. The technical expertise employed in playing the plucked-stringed instruments is very high, particularly when compared to the development of the punto filo.

[end of extracts]

Other reviews:

Muzicfan.com

For students of musicology who like some weighty matter to go along with their listening, look no further than Dr Olavo Rodriguez’s beautifully presented package: FROM AFROCUBAN MUSIC TO SALSA, a 180-page book and CD from the Piranha label out of Germany. Dr Rodriguez covers the main categories of Cuban music and you can hear fine examples of each of the styles he discusses. The design of the book is relaxed and handsome and a far cry from the frenetic junk that ruins so many CD booklets, rendering them illegible. The musical selections include four Afro-Cuban chants, five examples of the son, including changui and son montuno, four rumbas, five orchestral danzons (some of them a bit creaky), including Ases del Ritmo and two selections from Charanga Tipica de Rubalcaba, and four songs described as El Punto Guajiro.

Piranha records (publisher, Germany)

This book is full in trend: If you don’t want to be left behind, you have to brush up on your homework on Cuba and avoid confusing guaracha with a pureed avocado dish! The musicologist Dr. Olavo Alén Rodriguez has written an interesting account of the history of Caribbean music. This handy compendium traces the developments from early ritual African rhythms to the big band sound of later years. A reliable guide through the jungle of the diverse Cuban music genres. Sit back and read, listen and simply enjoy!

Leave a comment